Ma’s next chemo session, with both of her drugs, didn’t go well. The side-effects were serious enough that she was in misery. By the middle of January 2015, her oncologist, while still being somewhat circumspect, had started giving us signals that she was beginning to experience complications.

In the latter part of that month, Ma was asked to have a blood transfusion because her hemoglobin levels were too low. We spent an afternoon together while she had two units of blood pumped into her. Her oncologist had told us he was going to hold off on giving her another dose of the drug combination, and go ahead with only one drug the day after her blood transfusion. The import of this change in strategy had made an impression on her. As we sat there in the little hospital room, while blood crossed into her veins slowly, she told me, “Lagta hai mera jaane ka time aa gaya“. It would appear that it is time for me to take my leave, she was saying. She was calm, somewhat rueful, and looking at me as if for affirmation. I knew what she meant, but I feigned ignorance, and she explained that not getting her drug combination meant her oncologist was giving up.

I rationalized the change in her oncologist’s approach to her, explained that the single drug had efficacy in its own right, and that the combination was not ruled out forever. In the back of my mind, I knew that the end was drawing near, although it wasn’t yet pressing up against the thin membrane that separates our daily existence from the vast unknown.

The next dose was administered in due course. We settled into what had become the new normal for us. Feeding Ma happened almost exclusively through her stomach tube, called a PEG tube. This short tube was directly connected to her stomach. The external end was closed during the time she didn’t need to be fed, and she could do anything she wanted to in her daily life. Feeding her was a matter of adjustments on her part and ours. Theoretically, this tube can be used to feed any type of food, as long as care is taken to ensure that the food is liquefied and does not stick to or clog the tube. In practical terms, making sure that the wearer receives the correct number of calories, and the correct mix of minerals, means food that comes in pre-mixed boxes from a pharmacy is the easier choice. We figured out that she needed to be fed at least 1700 calories to maintain her weight, and that pouring the food into her tube too quickly made her very uncomfortable. Eventually, we became relatively good at providing nutrition through this tube.

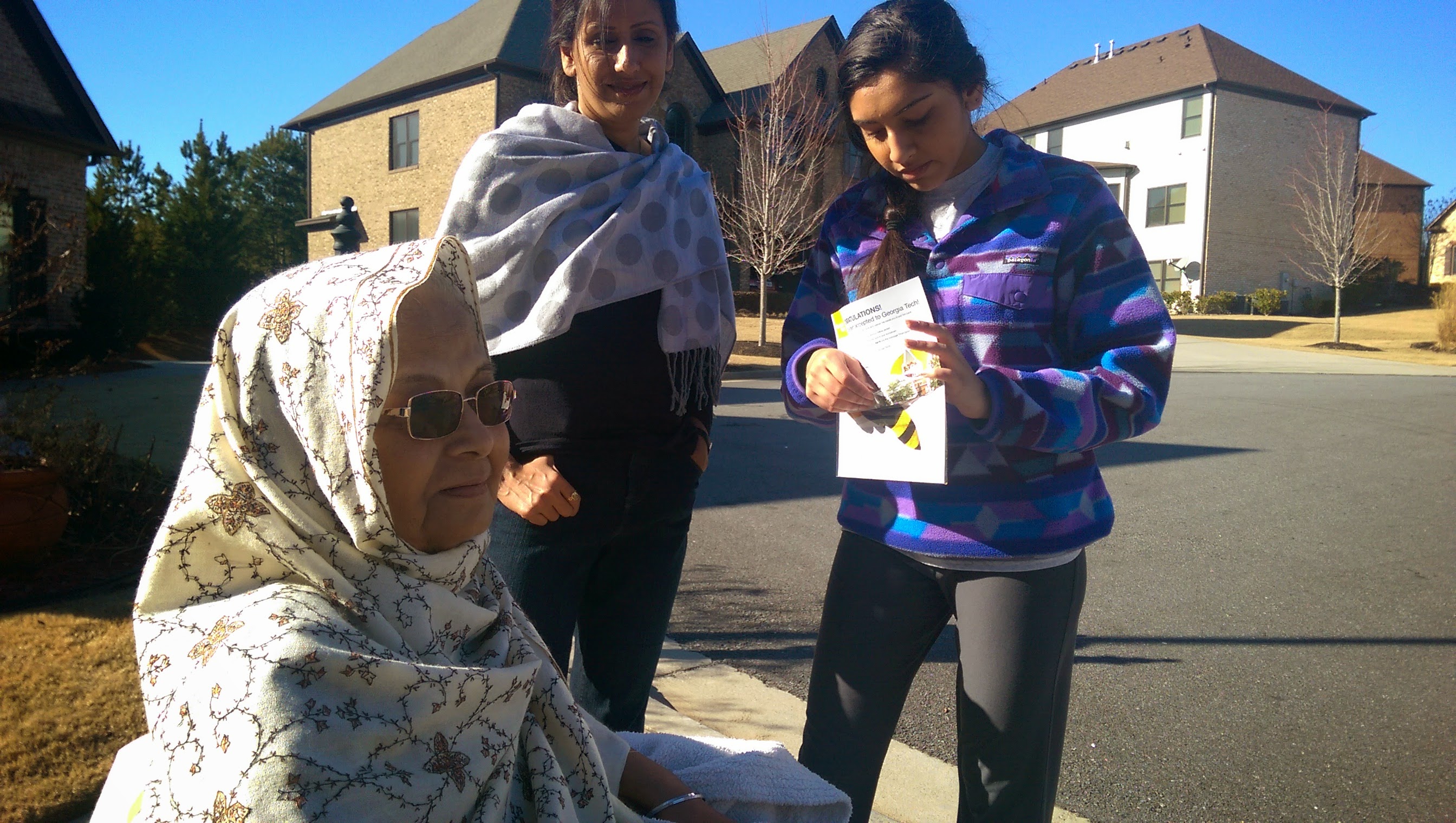

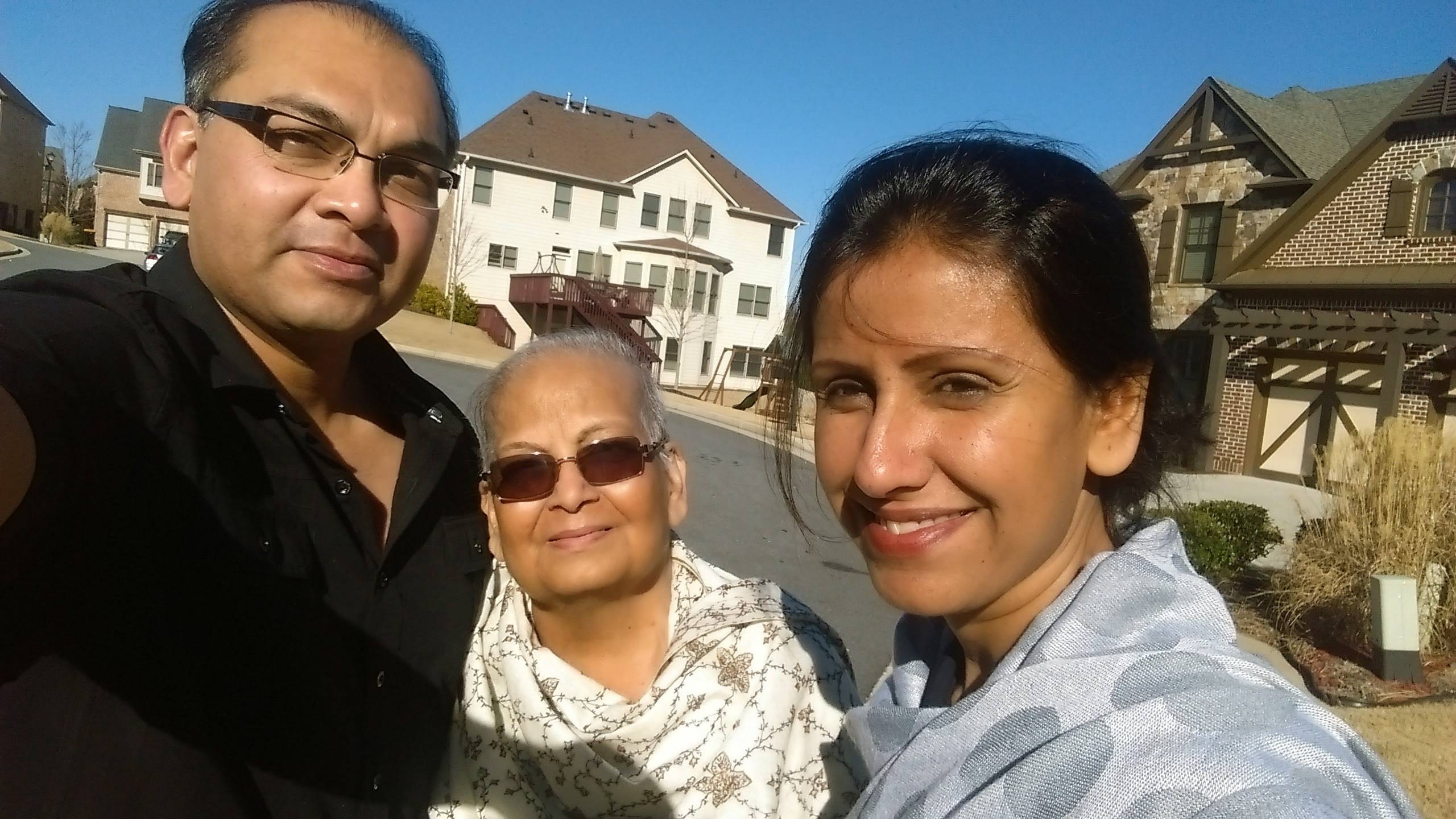

It was February 7, a Saturday. Her next chemotherapy session was now almost due. The weather had warmed up, and with the sun out in all its glory, it was easy to forget that it was still supposed to be winter. All of us, including Ma, came out of the house and soaked in the sunshine. Here are some photos from that day:

The 9th of February brought a sharp reminder that outward appearances could be very deceiving. She didn’t feel well that day, and Bhavya and the rest of the family took her to her oncologist for a scheduled checkup. Her oncologist examined her, and told us that her chemotherapy had failed to slow the progress of her disease. The only chance she had now – even if it was a very temporary fix – was to have radiation therapy to shrink the tumor around her throat, near her right collarbone. This tumor had grown and spread its tentacles all around her windpipe and foodpipe, as well as almost enveloped her spine. I was driving to the hospital a little later when my uncle, a former doctor who lives in the UK, called me on my phone. On hearing the news, he asked if I understood what was happening – that she was rapidly approaching her last few days. We were so used to staring death in the face by now that his words did not come as a shock, and I replied with a yes.

Her radiation therapy was to be carried out in a clinic that specialized in this type of therapy. Ma was to be taken there so that they could map the location of her tumor in their radiation machine. Once that mapping was executed, she would be able to receive therapy by being strapped into a machine which would move around her to radiate the tumor very precisely.

In recent weeks, Ma had taken to sleeping in a half-seated position, because lying down made her anxious about being able to breathe. She would go to sleep and sometimes relax and lie down fully, but wasn’t comfortable with maintaining a supine position in a waking state. It was as though her body was capable of breathing when she wasn’t thinking about it, but any conscious thought triggered anxiety and a consequent issue with breathing. This was a problem for her mapping for radiation, because she needed to lie down to have her tumor mapped. She tried several times, and the radiation staff tried very patiently with her, but she simply could not lie down for more than a few seconds. The mapping needed her to be supine and stationary for several minutes. Eventually, the doctor figured out a way to have her sit up the way she usually went to sleep, and modified the mapping process to adjust for the change in position.

For months now, Ma had been getting anti-anxiety medication. This medication, called Lorazepam, worked very well on her and allowed her to be calm so that she could sleep and behave normally. As one would imagine, being told that you have a terminal illness plays havoc on one’s mind, so she had received a lot of relief from this medicine.

The next day, she was driven to the radiation clinic again, this time to receive her first dose. The radiation would need her to lie down for one minute. Her ambulance got her to the clinic a few minutes before I could get there in my car, and they started the process of putting her into the correct position.

When I got to the radiation area a few minutes later, she was sitting up, fighting all attempts by everyone, including Papa, to get her to lie down. Apparently, that had been going on for several minutes, and the staff at the clinic were on the verge of giving up on her. Her gaze fell on me as I ran in, and relief took over her fear immediately. I went over to her to hold her. “Babloo re Babloo, bacha le hamra“, she said to me in Maithili, our mother-tongue. She was asking me, Babloo, to save her life, both because she couldn’t breathe lying down, and because she didn’t know what was going on. My eyes teared up. I could feel a huge lump in my throat. Holding her, I spoke to her very softly, and told her I was there to make sure nothing happened to her. Gently, I helped her into a supine position, and assured her she would not have to be in that position long, that we’d be watching her from just outside the door. All she needed to do, I said, was to be in this position for one minute. After that, I would come and get her up myself.

The staff was waiting for this. We all ran out of the room to not waste any time. As soon as we were out, they closed the room’s door to stop radiation from spilling out. Ma was visible on a monitor. One of the nurses asked us to talk to her through a microphone so that she would know she wasn’t alone. We started talking, Papa and I, telling her to be absolutely still, that the radiation had begun, that it would be over soon. My brave mother, hanging on by a thread to life, didn’t move, just waited for the ordeal to end. She obviously couldn’t breathe, because just as the one minute mark came up, and we were told her radiation was done, her arms went limp and fell off the sides of the narrow radiation table. She had passed out.

All of us ran in. I picked her up and placed her in a seated position, and the staff got an oxygen mask on her. She came to almost immediately. That, as you may imagine, was a huge relief.

She had another radiation session the next day, and this one went a little better. She was able to lie down for the minute required, although, again, I noticed that sometimes she seemed to not know where she was or what was happening. She was also forgetting the names of everyday things, and replacing them with completely strange names. For example, her favorite nasal decongestant, Vicks, became ‘plastic’, probably because there was a plastic foil right under the cap in the bottle. Bhavya and Malvika used to go to Zumba class, and that became the ‘bumba’ class first, and then changed to the ‘bamboo’ class. We had fun with her about this, but it was also worrying.

I was preparing to go to her radiation session on February 12, at about 9 am. She was ready to go, and went to the bathroom to get her things. I was waiting in the family room. As she opened the door of the bathroom, and started walking towards me, I could see confusion and concern on her face. Her breathing was very labored, and she looked ready to collapse. “Pata nahi kya ho raha hai, saans nahi le paa rahe hain (I can’t breathe, I don’t know what is happening)!”, she said. Shocked, I hurried to her, and told her to calm down, that I wasn’t going to let anything happen to her. I physically picked her up and set her down in a reclining chair. She was barely able to catch her breath. It was time to call an ambulance.

The ambulance came and took us initially to Gwinnet Medical Center in Duluth, since she was supposed to see her oncologist within that hospital system at a different hospital that day. She was given oxygen on the way. After going into Emergency at the hospital, the doctors and nurses gave her breathing treatments to open up her airways. She settled down into an easier breathing pattern. She was x-rayed and given a CAT scan. The results were not good at all. Her cancer had grown, and her windpipe was now barely open. The hospital sent her to their other facility, in Lawrenceville, where her oncologist was going to admit her and give her medical attention.

Gwinnett Medical Center in Lawrenceville is about as different from Emory Johns Creek, where we had been taking her for emergency care, as two hospitals can be. Emory Johns Creek is in an affluent suburb, with no obvious pressure on its facilities. Medical personnel and patients seem to be relaxed. Gwinnett Medical in Lawrenceville, on the other hand, receives a lot of low-income patients, its facilities are older and cramped, and everyone seems to be anxious. We arrived at the Emergency department at Lawrenceville hospital, took a number to get in line, and started waiting. Ma at this point was in a wheelchair, and was breathing with the aid of an oxygen mask.

After three hours, we were still waiting for a hospital room to open up. This was frustrating on many levels, main among them being that Ma was seriously ill and shouldn’t have been made to wait for medical care. Her oncologist, Dr. Krishnamachari, despite being in a building about 100 meters away, hadn’t shown his face or called us for the entire time that she had been waiting. At about 7 pm, I got angry and started walking to his building to get some idea of how long Ma would have to wait, and what was going to happen to her. I found him walking into Emergency and talked to him briefly. He assured me he was going to talk to the Emergency physician who would look after Ma, and ducked into a door. After about 30 minutes, Ma was finally taken inside, and put in a small room, where they started hooking her up to equipment.

In the bustle, I managed to find Dr. Krishnamachari again. He had just talked to the physician in attendance, and they had looked at her most recent scans and reports. His demeanor was serious, as was the message he delivered. He told me that Ma’s chances had gone from bad to worse, and that she was at the very end of her life. Hospice care is a system of providing end-of-life care to people who are not expected to recover, and its focus is on keeping patients comfortably sedated during their last days, as they wait for death. He said he wanted us to seriously consider putting her in hospice care, because she was not expected to recover, and would last a matter of days. The cancer in her throat, the one that had only just started receiving radiation, was throttling my mother to her death. Dr. Krishnamachari delivered this news, and told me that he was on vacation for the next several days, but someone in his practice would be in touch with us.

With this grim reality facing us, none of us were in any condition to put much thought into anything. Events had overtaken us. We were being thrown this way and that, with little control over what was happening, or was about to happen. That night, Ma stayed in the little room in Emergency until about 2 am, until a room opened up in the hospital. Dabloo stayed with her all night.

The next day, we congregated in the hospital. There was a general sense of gloom, now that the end was near. Several doctors came by, and Ma was getting frequent breathing treatments, which are steroid-based inhalants that open up the windpipe and lungs. Her mental state was actually remarkably good, due almost entirely to her being under the influence of anti-anxiety medication. She was very chirpy, busy recounting old stories that we couldn’t always tell were completely based on fact. I have a video of her telling one of these stories, and when I look at it now, I am not sure whether she was genuinely flighty or trying to fight her fear.

By mid-afternoon, the process of taking her home and putting her into hospice care was moving ahead. Dabloo had returned to the hospital by then, having had a few hours of sleep. Papa, Dabloo, and I were talking to a doctor who managed palliative care, and as he described to us what the next steps would be, something that had been bothering me bubbled to the fore.

“Why are we so focused on assuming this is the end?”, I asked. “She can’t breathe, but she was also told that radiation therapy will shrink the tumor and allow her to breathe. All she needs is time for radiation to happen. Why aren’t we thinking about solving that problem, by putting a breathing tube into her throat? I know people have those tubes and breathe through them for years, so why can’t she have that?”

The doctor looked at me as if he was surprised. “Is that what you would like?”, he asked. And at that moment, I realized what was happening.

Taking care of a terminally-ill relative is expensive and time-consuming. Most people, despite the best of intentions, are at the end of their rope in a few weeks or months. We had been doing it for about 7 months by that time. Insurance companies and hospitals have figured out that it might be worthwhile to suggest the easy way out of this situation by suggesting hospice care, but by couching it in the language of inevitability. If they do that, the patient’s family doesn’t feel like they gave up, and the commercial interests of the entities involved are also nicely fulfilled. In a ghoulish way, some might consider it a win for everyone concerned. We obviously weren’t one of the families which would go along.

“Yes! Of course!”, I replied. Papa and Dabloo looked relieved. We had just bought Ma some much-needed time. The doctor promised to get a surgeon to come and visit us very soon.

We went back to Ma’s room and explained what was going to happen. She didn’t really understand what we said. Our conversations at that point were amusing, except that they were happening with a person who was near-death.

Dr. Browning, an ENT surgeon came by to visit Ma and to talk to us. When he came into the room, Ma was having her feet massaged by one of us. He introduced himself, examined her, and then asked to speak with us outside the room.

Out of the many doctors we came across in Ma’s long journey, Dr. Browning was probably the kindest. He started talking about how he had gone home the night before, very tired, and his teenage daughter had offered to rub his feet for him when he lay down, and that had caused him to go to sleep. His eyes teared up at the similarity of the love surrounding Ma, and I was very touched. For the first time, we had met a doctor who saw Ma not only as a patient, but also as the target of so much love, concern and respect. He told us that she was definitely not going to survive more than a day or two, but he didn’t see that being asphyxiated to death by a tumor was at all humane – at least, he wouldn’t want a member of his family to go like that. He told us he would operate on her in the morning.

I stayed with Ma that night. Despite so many breathing treatments, she wasn’t able to lean back even a little to relax or go to sleep. The entire night was spent with her sitting up, sometimes dozing off slumped forward, and sometimes talking to me. At one point during the night, in her confused state, not knowing where she was but only aware that she was with her son and that it was late, she put my head into her lap, told me to relax and go to sleep, and started singing me a lullaby that I remembered from my childhood long ago. As you might imagine, that was a very emotional experience. Just writing about it moves me.

Morning dawned, and she was taken into the surgical preparation area. I was in there with her. The team of three anesthesiologists started preparing her, while also asking her questions about her life to put her at ease. One of them had some discoloration on his bald head, and when he took his cap off, Ma’s attention was immediately riveted by what she thought was a very funny sight. “What’s wrong with your head?”, she asked the man, smiling. He didn’t find the question funny, but the other two anesthesiologists started laughing and asking him, “Yes, what IS wrong with your head?”. I apologized on Ma’s behalf and came out as they made her comfortable, with a sedative going into her through an IV drip they had inserted into her earlier.

Here is her photo from that room. Note the puffy face and happy, medication-induced, look!

The family had all arrived by that time. I went home for a shower and change of clothes, and was back a few hours later. In the meantime, I kept getting updates from the hospital. She was out of surgery and resting in her room by the time I returned.

Since the breathing tube is placed under the voice box, there is no flow of air through the voice box – all the air is breathed in and out through the new hole in the throat, with the consequence that people lose their ability to talk.

When I walked into Ma’s room, she looked like a different person. Gone were the big problems: the difficulty breathing, the inability to lie down, and the look of uncertainty and fear. Now she looked relaxed, happy, and rested. Here is what I saw:

Dr. Browning had told my family that the surgery had been difficult because of the advanced size and growth of her tumor, but that she was in good shape to breathe. He had also been very moved by her repeated requests to see her family before she succumbed to anesthesia. When you are under so much stress, and you see someone empathize with you, when you see someone save a loved one’s life, there are no words to describe the emotions that well up. Suffice to say that we will be eternally grateful to Dr. Browning.

Ma was also back in her senses. I found out later that she had just become aware that she had lost her ability to speak, now that her mind was not clouded by medication. She had no idea that she had been written off by her medical team, nor that she was still close to death. One thing had changed, though: she now had a fighting chance, at least for a brief window.

One response to “Chapter 6 – Keeping Death At Bay”

Good to see her smiling face even when she is going through tough times. After reading this I can understand your attachment with her.